Washington, D.C., 1946: Humanitarian Food Relief for Occupied Germany

In 1943, US President Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the creation of the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA), an international organization designed to aid European refugees. Supported by 44 member states, UNRRA worked alongside other voluntary relief organizations to distribute food, medication, and other necessities to the liberated and displaced populations of Europe. None of these organizations, however, were permitted to provide assistance to German civilians. In addition to restrictions on relief, military officials also upheld a wartime ban on food imports, further exacerbating existing food shortages. In early 1946, President Harry S. Truman controversially reversed earlier policy and permitted food shipments for the civilian population. Truman also publicly endorsed the Council of Relief Agencies Licensed to Operate in Germany (CRALOG), and allowed the organization to solicit charitable donations for German relief.

The question of German food relief was embroiled in debates over occupation policy, namely enforcement of a “hard peace”—strict measures designed to remind Germans of their defeat and avoid repeating mistakes thought to have been made in the aftermath of World War I. As a result, Military Government prohibited the import of food to the US Zone in accordance with the Trading with the Enemy Act, which restricted trade with hostile nations. Roosevelt supported punitive measures in Germany, including limits on humanitarian aid. Concerned that German civilians would receive the same treatment as liberated populations, he believed soup kitchens an apt solution to food shortages. In 1944, Roosevelt’s Treasury Secretary and close friend, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., wrote a memorandum outlining plans for a harsh occupation, including the deindustrialization and partition of the country. The Morgenthau Plan faced opposition both within Roosevelt’s cabinet and abroad. While never officially adopted or endorsed, it was discussed at the Second Quebec Conference in September 1944, and influenced the first general order on US policy in Germany, Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) Directive 1067.

JCS-1067 sought a reduction in German standards of living, dictating limits on agriculture assistance and industrial production. It also established the “disease and unrest formula”, which acknowledged the food shortages and allowed for relief measures only if necessary. The formula, conceived by nutrition experts, established 2000 calories as the standard daily consumption required by normal consumers to avoid the spread of disease and civil unrest—potential threats to military security. This standard shifted dramatically once officials recognized that local food supplies could not support it. Germany had never been self-sufficient and had rationed food from the outset of the conflict. Even still, by the end of the war food stocks had been depleted, fields burned, and livestock slaughtered. Military Government personnel faced shortages in supply, manpower, and information, and spent most of 1945 adjusting consumer rations without much needed food imports.

Officials, including Military Governor General Lucius D. Clay, maintained that hunger was a corollary of defeat, but grew increasingly wary that food shortages could evolve into a food crisis. Clay warned that in addition to the negative physical and psychological effects, ration decreases revealed inconsistencies in policy that threatened the victor’s reputation. In August 1945, President Truman asked former director of censorship Byron Price to study Allied policy in occupied Germany. Following a ten-week tour of the defeated nation, Price published a report critical of the US and urged a reassessment of existing policy. Included in his recommendations was an increase in rations from 1550 to 2000 calories a day, which necessitated food shipments. Addressing critics, Price emphasized that this increase would improve the safety of occupying forces and protect the fragile health of Allied populations who were susceptible to outbreaks of disease. British officials reached similar conclusions and allowed food imports in October 1945, believing an increase in rations would stabilize the occupation.

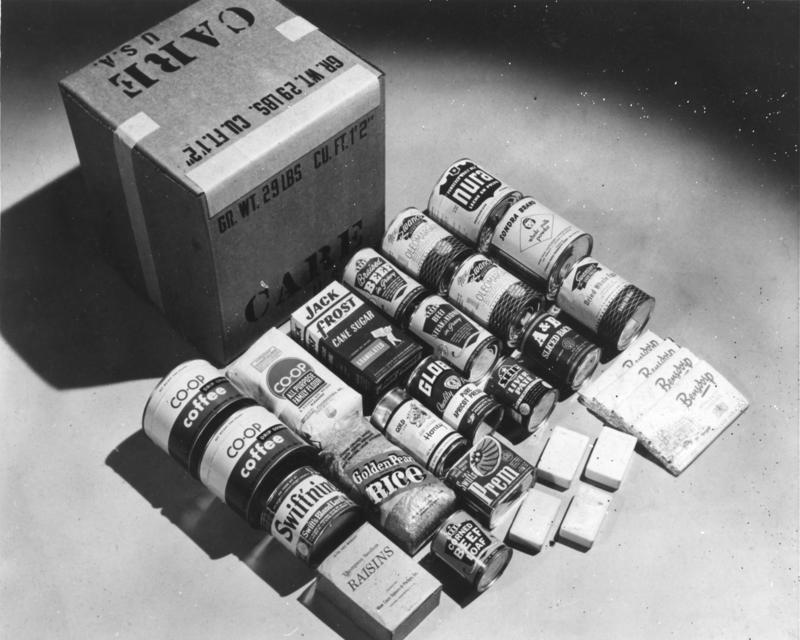

Throughout the summer and fall, representatives from several American voluntary agencies traveled to Washington to demonstrate their willingness to extend services to German civilians, lobbying members of Congress, and the State and War Departments. Their persistence paid off when the President’s War Relief Control Board approved an inquiry into the German food situation. In December 1945, a team left for Germany tasked with studying the nutritional needs of the conquered nation. This team traveled throughout the western zones, meeting with Military Government and leaders of German welfare organizations. The concluding report documented inconsistent and low rations alongside personal accounts of hunger. Facing increasing scrutiny, the White House announced monthly shipments of relief supplies to German ports, with Truman designating CRALOG as the only authorized agency to receive American donations for German relief. CRALOG was an umbrella organization that arranged for the shipment and dispersal of products collected by member agencies. Once the materials arrived in Germany, they were distributed by local social welfare organizations. CRALOG’s efforts in Germany were supported by the Cooperative for American Remittance to Europe (CARE), an organization created in late 1945 that offered a package service between Americans and Europeans in need. Humanitarians not only pressured the American government to change existing foreign policy, but also convinced the American people to support humanitarian aid for the former enemy. Both CRALOG and CARE underscored the democratic nature of the enterprise, emphasizing the importance of people-to-people aid and the responsibility of the US not only to keep the peace, but ensure that relief would lead to recovery.

Truman’s endorsement of CRALOG reflected the transition from a punitive to rehabilitative occupation policy, providing the foundation for an improved US-German relationship. Food aid to Germany underscored America’s humanitarian obligations and generated good publicity, swaying public opinion on the home front and in the former Reich at a critical moment in the early Cold War. Food shortages would continue to plague the western Zones throughout 1946 and 1947, leading to further ration decreases and unrest. The decision to feed Germany, however, was an important step towards economic recovery, paving the way for the Marshall Plan in 1947.

As the Cold War progressed, food emerged as a powerful tool of diplomacy, shaping American understandings of humanitarian assistance and offering “soft power” resistance in the fight against Communism. While the relationship between food and development remains essential to any history of US food aid, recent scholarship has pushed the narrative beyond the familiar periodization of the 1960s. As Nick Cullather has demonstrated, World War II was a turning point for international development and food diplomacy. Historians of postwar Germany have explored links between food and identity that highlight both the practical and symbolic power of American food aid. A closer look at events in postwar Europe yields important insights on the origins of modern American relief programs, particularly the impact of that relief on recipient populations.

Further Reading

- Cullather, Nick. ‘The Foreign Policy of the Calorie.’ American Historical Review 112, no. 2 (April 2007): pp. 337-364.

- Enssle, Manfred J. ‘The Harsh Discipline of Food Scarcity in Postwar Stuttgart, 1945-1948.’ German Studies Review 10, no. 3 (October 1987): pp. 481-502.

- Farquharson, John E. The Western Allies and the Politics of Food: Agrarian Management in Postwar Germany (Leamington Spa, UK: Berg, 1985).

- Forsythe, David P. ‘Humanitarian Assistance in U.S. Foreign Policy, 1947-1987.’ In The Moral Nation: Humanitarianism and U.S. Foreign Policy Today, edited by Bruce Nichols and Gil Loescher (Notre Dame, IN: Notre Dame University Press, 1989): pp. 63-90.

- Grossman, Atina. ‘Grams, Calories, and Food: Languages of Victimization, Entitlement, and Human Rights in Occupied Germany, 1945-1949.’ Central European History 44, no. 1 (March 2011): pp. 118-148.

- Steinert, Johannes-Dieter. ‘Food and the Food Crisis in Post-War Germany, 1945-1948: British Policy and the Role of British NGOs.’ In Food and Conflict in Europe in the Age of the Two World Wars, edited by Frank Trentmann and Flemming Just (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006): pp. 266-288.

- Weinreb, Alice. Modern Hungers: Food and Power in Twentieth-Century Germany (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017).

- Wiggers, Richard Dominic. ‘The United States and the Refusal to Feed German Civilians after World War II.’ In Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, edited by Steven Béla Várdy and T. Hunt Tooley (Boulder: Social Science Monographs distributed by Columbia University Press, 2003): pp. 441-466.

Short Biographical Note on Contributor

Kaete O’Connell is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at Temple University. Her dissertation examines US food relief in occupied Germany, exploring the role of compassion in diplomacy, the political currency of humanitarian aid in the postwar, and the symbolic power of food and feeding in occupied territory. Kaete was a participant of the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2017.