Kazan, 1921: Humanitarian Relief, Development Ideology, and The American Relief Administration’s Intervention in Russia

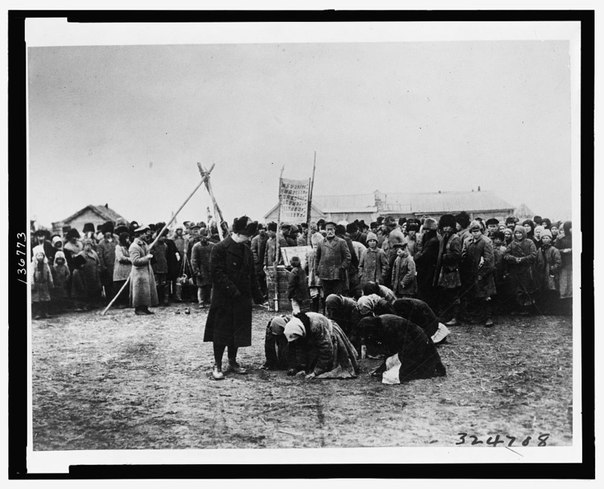

While on an exploratory mission to the Russian city of Kazan in the newly created Soviet Union, three American Relief Administration (ARA) aid workers — Bill Shafroth, John Gregg, and Frank Golder — were stunned by the devastation caused by famine. Looking out from their train car into the city, the aid workers saw hundreds of starving Russians crowded around the platform. This crowd consisted mostly of children living in abandoned railway cars, bellies distended from malnutrition waiting in the railyard for, in Shafroth’s words, a way out to “some mythical land of bread and honey.” The Russian escorts traveling with the relief workers informed them that these children were not locals, but refugees fleeing even worse conditions in rural regions.

The conditions in Kazan in 1921 far surpassed anything that the aid workers had encountered in their previous work. Shafroth, Gregg, and Golder were not new ARA recruits either; each of the men had served in Europe after World War I, delivering food aid to the nations of the former Central Powers. Conditions worsened in the city proper—hospitals and orphanages were overflowing, starvation was ever-present, and refugees crowded all available spaces. The trio of workers quickly contacted the nascent ARA command structure in Moscow and informed their superiors of the extent of the crisis. The refugee crisis, in particular, stunned the ARA men—their message to Moscow emphasized the number of refugees, and the need for the ARA to ameliorate the problem. From their first days in Russia, the ARA workers knew that this project would be something different, it would require a response on a different level from their previous work relieving Europe. Those three relief workers entering Kazan represented the first foray of any aid institution into the newly created Soviet Union. Their actions in Kazan, and the subsequent deployment of the ARA’s massive resources in the country, demonstrated the growing power of the U.S. state to influence overseas politics through non-military intervention, as well as illuminating the complex relationship between humanitarian relief and development projects.

When the trio of ARA workers ran their news up the line, it eventually reached “the Chief”: Herbert Hoover. Originally a mining engineer, Hoover proceeded to found humanitarian organizations during World War I and, once the United States entered the conflict, President Woodrow Wilson appointed him head of the U.S. Food Administration. In January 1919, Hoover used a congressional appropriation of 100 million dollars to convert the Food Administration into the ARA, the largest aid institution in the world at the time. The ARA operated with an intensely hierarchical organizational structure where authority flowed down from Hoover into the managerial level of analysts and bureaucrats and, finally, to the aid distributors on the ground. By the time that the ARA entered Soviet Russia, they had already distributed over one billion dollars worth of food in Europe and the Middle East over three years, funded mostly by the U.S. government. This type of work fell into a category most often associated with “relief”: the delivery of food and basic medical aid. When the ARA responded to calls for aid from the new Soviet Union, Hoover and many of his men in New York believed that their work would differ very little from their previous work in the former Central Powers. But, as Shafroth, Gregg, and Golder indicated, conditions merited a much bigger intervention. In response, the ARA initiated a new type of relief process in the Soviet Union, one that attempted to solve food scarcity through long-term, development-based solutions.

Russia presented a unique opportunity for Hoover’s ARA. Widespread famine in the country hardly made the ARA’s venture a bygone conclusion. When asking for famine relief in May of 1921, Russian author and Lenin confidante Maxim Gorky first reached out to the League of Nations and the League Coordinator for Humanitarian Relief Fridtjof Nansen, on the belief that Nansen represented one of the only humanitarians in the world who would voluntarily aid the Bolsheviks. His hesitancy was not unfounded. Hoover himself virulently opposed Bolshevik ideology. Hoover spared no criticism against the Bolshevik government, characterizing the Soviet Union in terms that would not seem out of place a half-century later during the Cold War. He labeled the U.S.S.R. “a tyranny” built upon “criminal instinct.” However, Hoover also saw an opportunity. He believed that socialism did not stem from politics, but rather social illness. The key to alleviating this illness, for Hoover, resided in remedying what he saw as “root causes”: famine, starvation, and disenfranchisement.

As a solution to the “problem” of Bolshevism, Hoover proposed what may be termed a “humanitarian intervention”, wherein his ARA would supply food, medical aid, and agricultural technologies to the Bolsheviks with the ultimate goal of upending the “root causes” of Bolshevism. This long-term process had two prongs, one based in geopolitics and the other in migration control as a developmental tool. First, the ARA began negotiations with the Soviet government to force farmers to stay in the famine struck regions along the Volga. The Soviets enthusiastically supported this plan. Second, the ARA brought their primary weapon to bear: food. The ARA distributed aid to the Russian population in the Volga region not solely based on need, but on the condition that farmers would continue working their farms rather than moving to the cities. Additionally, the ARA distributed extra seeds and farming equipment to the starving Russians in the countryside in order to facilitate agricultural growth and, more importantly, maintain population levels among the farming communities. These two tactics in tandem enforced sedentarization among the Russian farmers, guaranteeing aid incentives for farmers in production zones who refused to flee to cities.

By the spring of 1923 relieving the Russian famine had become the ARA’s largest single endeavor with over 300 American staff delivering 70 million dollars worth of food. As an extension of the power of the U.S. state, the ARA exerted enormous control over hundreds of thousands of peasants, farmers, and refugees in the Soviet Union. The ARA had sedentarized over 800,000 Russian farmers, restricting movement in the countryside in order to ensure sufficient crop production. The ARA had also transformed the very essence of their organization in Russia. In the countryside along the Volga River, ARA managers and young distributors re-oriented the scope of the American Relief Administration from simply famine relief to a larger and broader vision of humanitarianism rooted in their own particular conceptions of the Bolshevik identity. In this vision, the ARA workers had the right and the duty to police mobility, restrict aid, and manage the Soviet population in order to relieve the famine in the long term.

The ARA’s humanitarian venture in the Soviet Union demonstrates three key shifts in the way that American organizations interacted with the world in the early twentieth century. First, although the ARA operated as a private organization, it received significant funding and supplies from the U.S. state. Although idiosyncratic in its hierarchy and leadership, the ARA operated as a vehicle for expressing the growing power of the American state outside of traditional diplomatic or military channels. Second, Hoover sought to use the ARA as a means to enact political and social change in Soviet Union and, despite the failure to overthrow the Bolshevik government, the ARA gained unprecedented amounts of authority within the U.S.S.R. based largely on the backing of the United States government. Although this intervention used food rather than weapons, it had enormous consequences on both Soviet politics and the lived experiences of Russian farmers living along the Volga. Third, this narrative displays the often-fraught relationship between relief and development.

In what historian Michael Barnett terms the “conventional story” of humanitarianism, philanthropic organizations fall neatly into the categories of emergency aid or long-term development projects based on the organization’s credos and goals. However, Barnett concludes, humanitarian institutions throughout history have “never limited themselves to emergency relief.” (Barnett, 5) The ARA exemplifies this overlap, operating in the interstices of these two seemingly disparate categories: they sought to reorganize political and social structures in the U.S.S.R. through the access granted by their ability to deliver food aid. The ARA’s work in Russia reveals the messiness of these categories. At what point during the ARA’s venture did their work transition from relief to development? When they brought in preventative medical supplies? When they offered to help rebuild the Soviet Union’s transportation infrastructure? This narrative of the ARA’s operations in the USSR shows that these categories can often be definitionally murky and, in many cases, dictated and negotiated by the workers on the ground and the “beneficiaries” of humanitarian aid. The American Relief Administration undoubtedly saved tens of thousands of lives through their work in the Soviet Union, but their work was not merely dispassionate and technocratic, as their own historians would write. Their humanitarianism had an ideology; their food relief had conditions; and their aid had a politics—one with enormous consequences.

Further Reading

- Adams, Matthew Lloyd “Herbert Hoover and the Organization of the American Relief Effort in Poland (1919-1923)”, European Journal of American Studies 4, no. 2 (Autumn, 2009) https://journals.openedition.org/ejas/7627

- Barnett, Michael. Empire of Humanity: A History of Humanitarianism (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2011).

- Irwin, Julia. Making the World Safe: The American Red Cross and a Nation’s Humanitarian Awakening (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

- Patenaude, Bertrand. The Big Show in Bololand: The American Relief Expedition to Soviet Russia in the Famine of 1921 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2002)

- Porter, Stephen. Benevolent Empire: U.S. Power, Humanitarianism, and the World’s Dispossessed (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016)

- Weitz, Eric. “From the Vienna to the Paris System: International Politics and the Entangled Histories of Human Rights, Forced Deportations, and Civilizing Missions,” American Historical Review 113:5 (December, 2008): 1313-1343

Short Biographical Note on Contributor

E. Kyle Romero is a Ph.D. candidate at Vanderbilt University. He studies the history of the U.S. in the world, in particular the entangled histories of humanitarianism and refugee politics in the twentieth century. His dissertation "Moving People: Refugee Politics, Foreign Aid, and the Emergence of American Humanitarianism" studies the complex relationships between American humanitarians, diplomats, and missionaries in the early twentieth century as they engaged with refugee crises in Europe and the Middle East. Kyle was a fellow of the Global Humanitarianism Research Academy 2019.