South-Kasai, 1960: ‘Advancing’ the nation as a peacekeeping endeavour

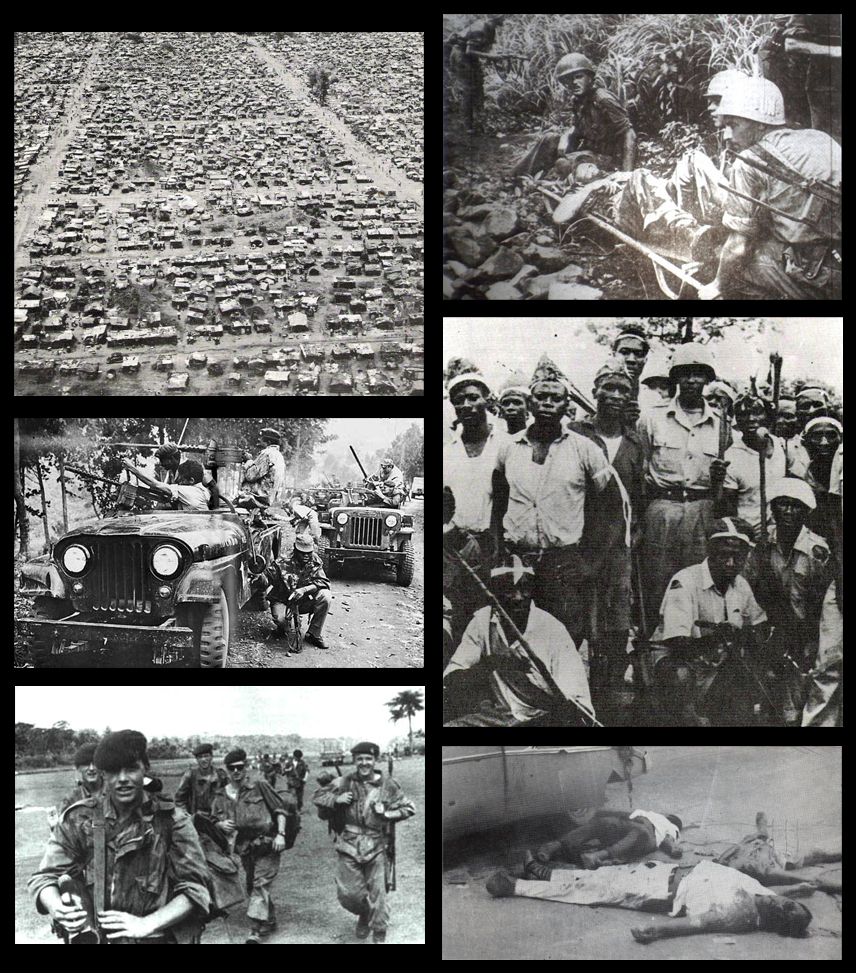

By late summer in 1960, the semi-independent southern region of South-Kasai had become a microcosm of the conflict in Congo. The clash of international actors, soldiers of the central Congolese army and secessionists in South-Kasai, in a region in Congo bordering Zambia, highlighted the instability and lack of governmental unity that lay at the core of the Congo crisis. In the months following Congolese independence from Belgian colonialism on 30 June 1960, the Congolese army (ANC) was regularly witnessed committing atrocities against resistant citizens in its attempts to maintain central Congolese control over multiple secessionist regions. Unable to maintain law and order, Congolese President Joseph Kasavubu and Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba wrote to the UN Secretary-General requesting support in removing Belgian troops from the country. The Security Council swiftly authorised the peacekeeping mission, Opération des Nations Unies au Congo or ONUC, with a dual administrative and military mandate on 14 July 1960. Despite this intervention, by September, the violence between the ANC and the South-Kasai secessionist troops had reached such heights that UN Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld publically referred to the ANC-perpetrated massacre of Baluba citizens, one of the main ethnic groups in South-Kasai, as “a case of incipient genocide”. UN experts feared that a famine, in addition to an already rapidly spreading epidemic of small pox, would follow the exodus of thousands of civilians from their homes as a result of the mass displacement and violence. However, despite a mandate of seeking Congolese unity and stability, Hammarskjöld was initially adamant in his refusal to allow ONUC to use force in any internal conflicts. In response to the unrest, the threat of starving civilians, and a lack of mandated access to military operations, the ONUC staff instead sought to influence the direction of the conflict and, concurrently, the ‘advancement’ of the country through their technical access to Congolese infrastructure.

Dag Hammarskjöld’s decision to bring the crisis to the attention of the Security Council and to, initially, prevent the ONUC mission’s military engagement with the secessionist conflicts established his personal involvement in the mission. Hammarskjöld’s decision to personally suggest the creation of ONUC has been reviewed by revisionist historian Pierre-Michel Durand, thereby challenging the orthodox sanitised interpretation of Hammarskjöld’s time as Secretary-General. Durand has sought to place this decision within the context of Hammarskjöld’s skill in ‘exploiting the imprecisions of the Charter’ to extend the power of his office (P. Durand, 2006, p. 56). Therefore, by taking such personal interest in the construction of the mission, Hammarskjöld’s cultivation of the ONUC bureaucracy meant that the overriding approach of the mission was controlled by a small group of Western technocrats. Despite his refusal to allow ONUC troops to engage with the secessionist movements in the south, Hammarskjöld and his staff saw technical assistance projects as a means of steering the country towards a liberal future without encountering the political baggage that would accompany ONUC battalion operations.

By prioritising his personal experience of personnel, Hammarskjöld chose many of the staff from careers that would have given them familiarity in colonial or ex-colonial environments. Prior to agreeing to be in executive control of ONUC’s technical operations, Sture Linnér was Executive Vice President and General Manager of the Liberian-American-Swedish Mining Company (LAMCO). LAMCO’s involvement in international extraction of African natural resources greatly influenced Linnér’s perspective on the rights, interests, and ethics of fellow European mining company, Union Minère, during its involvement in the Congo crisis. Tellingly, LAMCO was chaired by Bo Hammarskjöld, the Secretary-General’s brother, suggesting the potential for cronyism within UN structures at this time. However, this policy of cronyism had deeper political significance than the recruitment of a family friend. Linnér has since spoken of his belief that UN staff joining the mission were chosen for ONUC to create a supposedly ‘civilising’ influence on the Congolese population and environment. Ashamed of his ‘primitive working conditions’ on the ground, Linnér hoped that the osmotic effect of the ‘aristocratic’ quality of the international civil servants (many of whom were part of Hammarskjöld’s diplomatic circles) would help to curb the chaos he saw on the streets of many Congolese cities (UN Oral History, 1990, p. 46).

Linnér’s perception of those on the ground indicates the detachment felt between those involved in the conflict: the civilian Congolese population, soldiers in the ANC, and ONUC peacekeeping staff. The ONUC mission’s construction of technical assistance projects—including educational classes, unemployment projects, agricultural schools and technical training – especially in the areas of airport control and radio stations—across Congo provided the UN civilian staff physical access to multiple areas of Congolese infrastructure and a wide range of the population. The apolitical and neutral rhetorical associations with ‘technical’ assistance gave the appearance of impartial delivery of socio-infrastructural support to the Congolese population, whereas the private correspondence between ONUC leadership reveals that each project represented an attempt to draw the newly-independent Congolese state into the liberal internationalist philosophy. Evidencing the state building intentions of the mission, one ONUC progress report noted with pride that the work had ‘gone well beyond the operative phase in the past month, to the point where it is having a wider and, if conditions permit, a long-term effect on the economic and social conditions of the country’ (United Nations Archive, S/PV.873, p. 32).

This state building policy was reinforced by the technocratic and exceptionalist policy of placing UN staff in roles vacated by fleeing Europeans. By installing staff from a range of specialised agencies within the UN—the World Health Organisation, United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, International Labour Organisation—and, externally, the International Committee of the Red Cross, Linnér encouraged his staff to do what needed to be done in order to ‘save lives’, regardless of whether it breached Congolese law or UN protocols. In one particularly striking example showing the lack of respect that Linnér and his fellow ONUC technicians afforded the Congolese army, they stole ANC trucks in order to supplement the UN’s deficiency in transport facilities. This attitude served to institutionalise the international actors’ exceptionalism from the ‘normal’ boundaries of appropriate behaviour due to the mission’s humanitarian mandate, highlighting the hypocrisy of the bureaucracy’s ‘civilising mission’. International agents under the auspices of the ONUC mission would intervene in the crisis, aid the Congolese ‘advancement’ through technical assistance, and maintain law and order. However, many would simultaneously break the UN’s own procedures and seemingly remake the rules of ‘civility’ without recognising the hypocrisy due to the guise of their humanitarian motivation. This technocratic and humanitarian exceptionalism helped to establish the international peacekeeping agents with an institutionalised, racialised impunity that had been inherited from a similar colonial dynamic of double standards. More broadly, the UN’s response to the Congo crisis speaks to fellow histories of humanitarianism that examine the paternalistic relationships between humanitarian/recipient, donor/beneficiary, and peacekeeper/civilian.

In response to the lack of historical literature examining the delivery of technical assistance in peacekeeping missions and as part of an effort to connect peacekeeping histories to those investigating liberal colonial projects, this entry builds upon the dynamics described in development literature to help illuminate the similarities of power structures within the delivery of ONUC technical assistance. The post-colonial, developmental turn in international bodies seeking to paternalistically ‘improve’ states they interpret as ‘failing’ is also visible in the language and choices made by the ONUC mission. Frederick Cooper’s analysis of development initiatives during decolonisation can also be used to highlight the paradox behind much of ONUC’s rhetoric during this period as they worked towards, ‘a modern future set against a primitive present’ (F. Cooper in Cooper and Packard, 1997, p. 65). Therefore, the ‘complex shift in vocabulary and the persistent narration of historical rupture’ did not encourage the leopard to change its spots (A. Biccum in Duffield and Hewitt (eds.), 2009, p.1). At the heart of development and social progress projects remained the same genus of paternalism that motivated nineteenth-century colonists in their ‘civilising missions’.

Further Reading

- Cooper, F. ‘Modernising Bureaucrats, Backwards Africans, and the Development Concept’, in F. Cooper and R. Packard (eds.), International Development and the Social Sciences: Essays on the History and Politics of Knowledge, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

- Duffield, M. and Hewitt, V. (eds.). Empire, Development and Colonialism: The Past in the Present, (New York: Boydell and Brewer, 2009).

- Durand, P. ‘Leçons congolaises: L’ONUC (1960-1964) ou “la plus grande des operations”: un contre-modèle?’, Relations internationales, Vol. 3:127, (2006), pp. 53-70.

- Macqueen, N. United Nations Peacekeeping in Africa Since 1960, (London : Routledge, 2014).

- O’Malley, A. The Diplomacy of Decolonisation: American, Britain and the United Nations during the Congo Crisis 1960-1964, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018).

- United Nations Oral History. ‘The Congo Operation: an Interview with Sture Linnér by Jean Krasno’, 8 November 1990, http://dag.un.org/handle/11176/89726 [15 April 2019].

Short Biographical Note on Contributor

Margot Tudor was awarded a First-Class BA (Hons) in History in 2016 and went on to complete an interdisciplinary MRes in Security, Conflict and Justice at the University of Bristol. In September 2017, Margot began her ESRC-funded PhD in Humanitarianism and Conflict Response at the University of Manchester. Margot was a participant of the GHRA 2018.